Android Experiments: Hashire Hamusuta Post-Mortem

It all began about 10 days ago when I first learned about the Android Experiments I/O challenge.

What is Hashire Hamusuta?

Hashire Hamusuta, Japanese for “Run Hamster”, is a game designed to encourage people to stay active. It was my entry for the challenge.

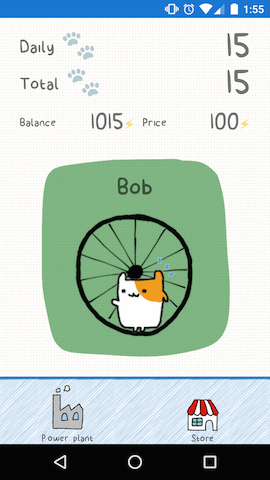

In the game, you’re a hamster. The hamster runs when you are active and sleeps when you’re not. When you walk, run, or ride, the app counts your steps and you earn ⚡.

You can spend ⚡ at the store to purchase hamsters, which will produce more ⚡ in your power plant.

In your power plant, you can ping lazy hamsters that are inactive. You earn a 100 ⚡ bonus if they become active within 10 minutes.

There is also a 10,000 daily steps goal. If a player achieves this, they earn 100 ⚡ for players who have them in their power plants.

Interface Design and Illustrations

I wanted the app to have a playful aesthetic, drawing inspiration from Neko Atsume.

Giorgia created all the illustrations, perfectly capturing the style.

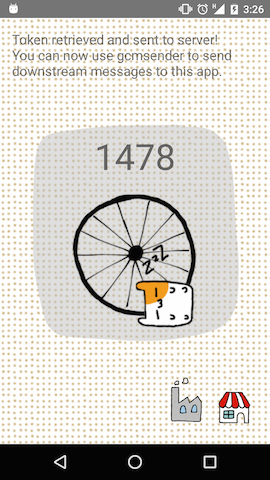

The first version of the app:

The latest version of the app:

Go and Google App Engine

I decided to try Google App Engine (again) to host the app server, which collects player information, step measurements, etc.

The platform supports Java, Go, and Python by default, but it also supports custom runtimes.

Initially, I attempted to use Haskell to build a simple Scotty HTTP API. However, after nearly half a day spent trying to build and run the container, I gave up.

Creating a custom Dockerfile should have been straightforward, but I encountered numerous errors. The container initially built too slowly using the Cloud Container Builder, resulting in a DEADLINE_EXCEEDED error, which I resolved by setting the use_cloud_build option to false to avoid using Cloud Container Builder. Then, I encountered docker errors that I can no longer recall. This poor start, combined with the idea of working on this project in hackathon mode (more on that later), led me to choose Go.

Apart from an issue with GOPATH and a problematic interaction between the official Go tools and App Engine SDK’s tools, everything else worked as expected using Go. Deployment of the app is fast and reliable, and managing app versions is easy.

Google Cloud Messaging

Pinging a friend involves sending an app notification to their device. I also wanted to display the live status of the hamsters (running or sleeping) in the power plant activity. To deliver and receive notifications, I used Google Cloud Messaging.

To deliver messages from the server, I used a patched version of github.com/alexjlockwood/gcm. By the time I discovered github.com/google/go-gcm, which I believe to be a more official and up-to-date library for interacting with GCM, it was too late.

The server publishes updates on a topic for each player. Clients subscribe to owned players’ channels to receive notifications when a new event occurs.

To handle notifications on the client side, I followed the example at github.com/googlesamples/google-services.

Acquiring Data from the Step Sensor

To obtain the user’s activity and number of steps, I first attempted using the Fit API. However, I couldn’t find a way to handle background updates of the user’s activity. I needed to gather this data in the background to notify the system and other users of the current user’s status changes.

Consequently, I chose to retrieve raw events from the step counter sensor with a background service inspired by github.com/googlesamples/android-BatchStepSensor. The result is quite reliable on the many devices where I tested the app, with a few exceptions.

Drawable Resources for Different Resolutions

I’m lazy, so I was placing all drawable resources in the res/drawable directory. Also, because I’m lazy, one day I didn’t feel like getting up to reach the USB cable to test the app on my phone, so I used the emulator. That’s when I started noticing numerous OOM errors.

What was leaking memory?

Well, it turns out that loaded drawable resources are stored as bitmaps in memory. So, a 100 Kb PNG image was consuming megabytes of memory to be displayed on the screen.

Moreover, all drawable resources placed in the generic res/drawable directory are treated as mdpi resources. Android by default scales the low-density drawable version to the target device’s density.

This meant that a 100 Kb 500x500 PNG image was being scaled to a 9 Mb 1500x1500 image on an xx-hdpi device (Nexus 5). The emulator was only reserving 64 Mb of RAM per app process, so I was hitting the limit after loading just a couple of images.

The workaround solution was to create a new res/drawable-xxhdpi directory and copy all the images there. The size was fine because I always tested the app on xx-hdpi devices.

Note: To reduce the app’s memory usage, I could have done this for all supported devices’ resolutions, but I’ll wait for actual crashes to address it.

What Went Right

- Go on Google App Engine

- Google Cloud Messaging

- Step counter background service

- Giorgia’s illustrations

What Went Wrong

- Haskell on Google App Engine

- Fit API

- Drawable resources resolutions

Hackathon Mode

What does Hackathon mode mean? Well, I’m not entirely sure. It’s an excuse to try new technologies on small projects within a time constraint.

The time constraint aspect is intriguing as it forces you to focus on the functional parts of the app to have “something” to test as soon as possible.

One useful approach is to work on the riskiest parts of the hack first. For example, in this project, I began by building a couple of Android prototypes to test GCM (👍), Fit API (👎), and Haskell on GAE (👎).